Revive Stronger

How a Powerlifter went from Lifting in Pain to Lifting PRs

It’s not uncommon for experienced lifters to pick up injuries along their lifting career, but what allowed Chris Janssen to go from being unable to squat without anguish to setting Personal Records on the platform?

I first started working with Chris in June 2015, at this time he just wanted to drop some fat and maintain as much strength as possible. He also expressed how he has been dealing with pain in his achilles and hip flexors, making squatting an issue. So Chris initially had the goal of fat loss and hoped to be able to find a solution to his pain, so he could do the lift he loved.

[bctt tweet=”Getting injured sucks — but not training is suckier”]

From the get go I put Chris on a 4 day per week programme, lowered the intensity but had him working with higher volumes. I also got Chris to start recording his Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE), so we could keep an eye on his fatigue levels, this combined with light days and deloads would hopefully enable us to manage pain/fatigue.

In addition Chris was given mobility guidance and was advised to do 10 minutes of mobility work after each workout. The idea was that this would help keep his injuries in check, and give us sometime to develop some work capacity before ramping up intensity, if Chris could manage it.

Of course this was used in combination with a calorie deficit and relatively high protein diet, to produce a calorie deficit enabling Chris to drop fat and maintain muscle and performance (I don’t want to go into depth on that in this article).

Chris responded better than we could have hoped for, he was able to squat and actually improved this along with his other lifts. He also lost over 20lbs, so pound for pound was the strongest he’d been too. There was an opportunity for him to compete in a local meet, and so we went for it, and that is what I am going to talk about today.

Table of Contents

Careful Exercise Selection

Chris and I over our time together had cycled in all the variants of the main lifts; sumos, conventionals, high bar, low bar — and we had come to the conclusion that the ones that were sustainable and we could progress best on were sumo deadlifts and high bar squats. Yes high bar squats, although Chris may have been stronger low bar at a time, the positioning was causing him too much discomfort and pain. So what ended up happening was the development of a fairly hybrid style of squat, not low enough to be called low bar, but not using traditional high bar form. You can see it below:

Sumo deadlifts allowed Chris to pull more, and importantly they didn’t cause any pain. It was essential that we were able to select lifts that would be specific to the sport of powerlifting and allow us to progress them, and that is why these were selected.

EXERCISES MUST BE SPORT SPECIFIC & PROGRESSIVE

Along side these competition lifts we also ran some assistance movements, some to help develop and maintain back, shoulder, hamstring and core growth and others were kept pretty specific by only being variants of the competition moves. As the competition neared the variants of the competition lifts were replaced with the competition lifts and the volume on the other non-specific powerlifting work was reduced, until in the final 2 weeks before the meet all assistance work was dropped.

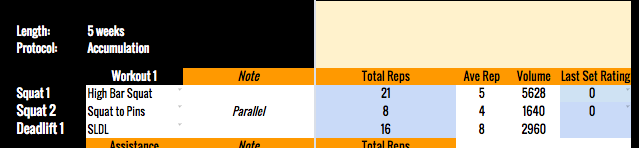

EXERCISES MUST GET MORE SPECIFIC CLOSER TO COMPETITION

For example during the Strength Block prior to Chris’s Peaking Block we had him performing squats to pins, straight legged deadlifts (SLDLs), front squats and over-head press — along with the main competition movements. These were used to help work on weaknesses (such as a Pinned Squat in the hole) and also to help reduce fatigue (by being underloading variants — SLDLs are lighter than deadlifts off the floor). So assistance movements were selected to work on Chris’s specific weaknesses and also prevent his hips getting wrecked.

Individualised Stress Management

As previously mentioned we had to be really careful as to not stress Chris too much, as it could leave him unable to train at all. Too many people put too little emphasis on stress management, and what usually happens is they either get injured or their performance goes down — either way they’re not progressing. So regardless if you’re nursing injuries or not, you need to use these strategies.

[bctt tweet=”If you cannot train — you cannot gain.”]

First of all we were sure to programme mobility work, as said before this started with 10 minutes post workout, focussing on his lower body. However, Chris took this further and was doing it in his own time, I have no doubt this was pivotal to keeping him healthy.

SPECIFIC MOBILITY WORK

During his Strength blocks we used light days, these were sessions where intensity was reduced and volume slightly. These allowed Chris to work on his form, and acted as a form of active recovery to further reduce stress. For example Chris would perform some lifts at 70% of his 1 rep maximum for multiple triples. By respecting the bodies ability to deal with stress we were able to provide Chris with sufficient overload and then recovery for him to grow and adapt to get stronger.

LIGHT DAYS USED IN COMBINATION WITH OVERLOADING DAYS

During our entire time working together we implemented deloads every 4 to 6 weeks. These are a week in length and are used to dramatically drop the fatigue built up over the weeks prior, and set Chris up for another 3 to 4 weeks of hard training. A typical deload used saw Chris drop his volume by around half and saw a slight drop in intensity, this is because volume is the main contributor to fatigue, and by keeping in some intensity Chris didn’t totally lose his groove.

DELOADS EVERY 4 TO 6 WEEKS

In combination with the above Chris tracked his fatigue levels and was working to given RPEs. So he was not pushing to failure every set and he would rate his fatigue at the end of each workout. For the most part we had Chris working with RPE 8s for his strength block, this meant he was a full two reps away from failure.

[bctt tweet=”To take 3 steps forward, sometimes you must take a few back.”]

Using this system we could auto-regulate, allowing Chris to make the most of the days he felt good and pull back on the bad days. Sure he was still working hard, but the lower RPE allowed him to accumulate more total volume and reduce the risk of injury. The weeks prior to deloads would be ramped up in intensity, and he would take his sets to RPE 9s and potentially hit some 10s — these are normally very hard to recover from, so they are perfectly timed before a deload.

MONITORING FATIGUE & RATE OF PERCEIVED EXERTION

After every session Chris would rate his overall fatigue, he would also check in with me weekly to give me more detail on how he was recovering and how his injuries were holding up. This enabled me to keep his volume at the right level for him, so he had enough to spur progress but not so much that he could not adapt and grow stronger. This has been referred to as your Maximal Recoverable Volume (MRV) which is essentially the amount of work you can do and still recover from week on week. Me and Chris therefore were able to keep Chris in and around his MRV via the above and then push slightly above it when was appropriate.

Personalised Peaking

When it came time to peak for the meet Chris had already come off the back of over 10 weeks of strength training, working with loads around 75 to 90% of his 1RM and reps landing within 3 to 6. These are the best intensities to develop strength and each phase of training saw Chris build intensity weekly in an overall linear fashion.

TO PEAK STRENGTH, YOU MUST FIRST BUILD STRENGTH

This was Chris’s first Powerlifting meet, so I knew it was essential to get him a lot of practice with heavy loads on his back, especially heavy singles. The Peaking Block used was 4 weeks in length, as already discussed we focussed only on the main competition lifts and had a few accessory movements for back, shoulders and hamstrings which were then removed from 2 weeks out.

We got ultra specific in these last few weeks leading to the competition, Chris would perform a heavy single for his main movements and then perform % drops for a given number of sets. For example the first week Chris performed a heavy back squat and then backed off 15% and performed a further 3 sets at an RPE 8. Each week the % we backed off would reduce, meaning intensity increased linearly. The frequent heavy singles were to allow Chris to get comfortable under heavy loads, and practice lifting under meet conditions (or as best as we could get). The back off sets were used to get in the required volume, and both the heavy singleS and back-off sets were autoregulated using the RPE scale.

DURING THE PEAKING BLOCK YOU GET ULTRA SPECIFIC

During this block frequency was high; Chris was benching and squatting three times per week and deadlifting twice. These were mentally challenging and really pushed Chris however; light days were interspersed to help reduce fatigue but allow Chris further practice the competition movements.

[bctt tweet=”Practice makes permanent “]

In the week leading up to the meet Chris only went into the gym three times, the first session we worked up to his openers and the final two sessions intensity and volume was reduced further to allow fatigue to drop heavily but keep everything fresh. This was to allow Chris to be in the best possible condition to lift come the day of meet.

Day of Meet

When it came to the day of the meet Chris felt incredibly confident and also very fresh. We had discussed what he would expect beforehand and he had a ‘Day of Meet’ checklist and warm up guide. Furthermore, there were no second guesses for Chris, we had developed a selection table that would help him pick his numbers. Lifting heavy especially for the first time at a meet can be a nerve racking experience so plan everything!

MAKE A CHECKLIST OF ITEMS YOU NEED FOR THE DAY

A photo posted by Chris (@chrisdoeslife) on

In this table it had three choices for each lift for the opener, second and final attempt. The choices Chris had were ‘feeling crummy’, ‘feeling average’ and ‘feeling good’ — the idea is to feel good but we wanted to have all bases covered. These numbers were based off his training history, we track everything from weight, reps and volume to RPE and fatigue — this gave us the information we needed to select the right weights.

In short his ‘feeling crummy’ final attempt would probably be 90% of his estimated 1 rep max; something he could do under almost any conditions. ‘Feeling average’ would be at his current 1 rep max, something he can hit most days. Finally his ‘feeling good’ numbers would have him set a personal record, around 102 to 105% of his 1RM. Chris was to warm up in exactly the same way as his warm ups during his peak week, this helped to keep everything nice and specific on the day.

PLAN YOUR ATTEMPTS BEFORE THE DAY

Ideally I would have been there with Chris to help him with his selection, so I could see how his warm ups were moving and his initial attempts. However, being that I am in London and Chris is in Missouri (USA) the approach we took was the best we could hope for. For first time lifters I think it is really important to build confidence, so our aim was to get a 9/9 and set a nice personal best, rather than doing everything we could to lift as much as possible.

[bctt tweet=”Failure to plan is planning to fail.”]

You do not know whether you bloom under the competitive environment or crumble. It’s like those kids who know all the answers to the questions in lessons, and do well on their course work, but when it comes to exam conditions they suck. Therefore without any meet history to go off, we were conservative. A missed lift is useless, so we don’t want any second guessing.

[bctt tweet=”A missed lift is useless”]

With all the prior months of hard training, precise programming and planning ahead Chris was in a very good position come the day of the meet. He actually lifted slightly more than our ‘feeling good’ total and produced a lifetime personal best. I am massively proud of Chris and he performed better than either of us could have hoped for, this will set the foundation for future meets.

Check out his performance below, I think your agree his technique was of a very high standard and he had more in the tank — I am excited for this mans future.

How to go from Injured to Setting PRs

Here I want to summarise what I have gone over, as I have covered a lot. Chris has done incredibly well over our time together, and I am very honoured to have him as a client, because he puts in the work, he checks his ego at the door and sticks to the plan. I know a lot of lifters who would get frustrated with deloads, taking light sessions, working to lower RPEs and possibly coming away from their favourite lifts, but Chris had the fortitude to stick to it, and it paid off big time.

-

Make sensible exercise selections.

-

Implement light days & deload weeks.

-

Auto-regulate and respect how you feel each day.

-

Plan and monitor and adjust as necessary.

If you do the above you will give your body sufficient time to recover and provide enough stress so you can lift injury free, and if the time comes, take that newly acquired strength to the platform and set records just like Chris.

- M, Israetel. J, Hoffmann. C, W, Smith. Scientific Principles of Strength Training. 2015

We are a personal coaching service that helps you achieve your goals. We want you to become the best version of yourself.