Revive Stronger

Is 5 Fruit & Vege a day enough?

Recently, you probably noticed a lot of discussion in the media about fruit and vegetable intake.

This was in light of a study [1] recently published which studied eating more than five portions of fruit and vegetables (400g) per day (the current UK and World Health Organisation guidelines). There was a lot of confusion about whether the guidelines had changed (they haven’t) and what the study meant in terms of our current understanding about the importance of fruit and vegetable intake for maintaining good health.

In this article, Emma Green hopes to clear up this confusion, as well as providing you with tools to be able to read and interpret research articles or even just adopt a more critical stance of the media presentation of scientific studies.

Table of Contents

So what did this study do?

The study was a systematic review and meta-analysis.

1.] A ‘systematic review’ means that the authors have searched for all of the previous studies that have been conducted on a particular topic (in this case fruit and vegetable intake) in a systematic way (rather than a quick and dirty google search!) and summarised what these studies have found.

2.] A meta-analysis goes beyond this and provides a statistical representation (a numerical value) of the findings of all the studies. This study explored whether there was a dose-response relationship between increased fruit and vegetable intake and future health problems (eg. is more better?). It is important to note that the study only looked at cardiovascular disease, cancer and mortality rates.

What did this study find?

The study found that reductions in risk for cardiovascular disease or dying from another cause was reduced for individuals consuming up to 800g of fruit and vegetables per day (the equivalent of 10 portions per day). For cancer, the benefits levelled out at intakes of 600g per day (7.5 portions per day).

So what does this mean?

There are several things we need to take into consideration about this review before making a firm conclusion, which I will discuss below.

How was fruit and vegetable intake measured?

Fruit and vegetable intake was measured through self-report in the studies in the review.

This is the most common way to determine intake in nutrition studies but can be unreliable. People may over-report the number of fruit and vegetables they are consuming each day (particularly if they are being asked about it by a researcher and they are aware of government guidelines). In addition, most of the studies in the review only asked people at one time point what their intake was and then followed them up to see if they became ill.

Very few studies asked people later in time what their intake was, so it cannot be known whether people’s intakes changed in between the time they were asked and when they became ill.

Correlation vs causation

There is a big difference between two things being associated with each other and two things being causally linked.

For example, walking in the gym is strongly associated with increased muscle mass. Does this mean that walking into the gym is inherently anabolic? No, it depends on what you do in the gym once you get there, as well as many other factors (calorie intake etc). There are many things which are associated with each other, which is known as correlation but this doesn’t mean that one directly causes another.

In terms of this study, we know that a higher fruit and vegetable intake is associated with a reduced risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease and mortality but not that fruit and vegetable intake causes this reduction in risk.

Marker vs independent risk factor

Following on from correlation vs causation, there is a big difference between something being an indicator and something being inherently positive or negative. Using the previous example, going to the gym is a marker for engaging in weight training. It is the weight training that contributes to the increased muscle mass not going to the gym.

Similarly, in this review, fruit and vegetable intake may be a marker for living a healthier lifestyle, rather than being an independent risk factor in itself. For example, people who eat more fruit and vegetables are more likely to be physically active, not smoke, drink moderately etc. Some studies in the review attempted to statistically account for these other factors but not all studies did this.

We can therefore not discount the possibility that these other factors contribute to the reduced risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease and mortality, rather than fruit and vegetable intake. Alternatively, both fruit and vegetable intake and these other factors may collectively contribute to a reduced risk.

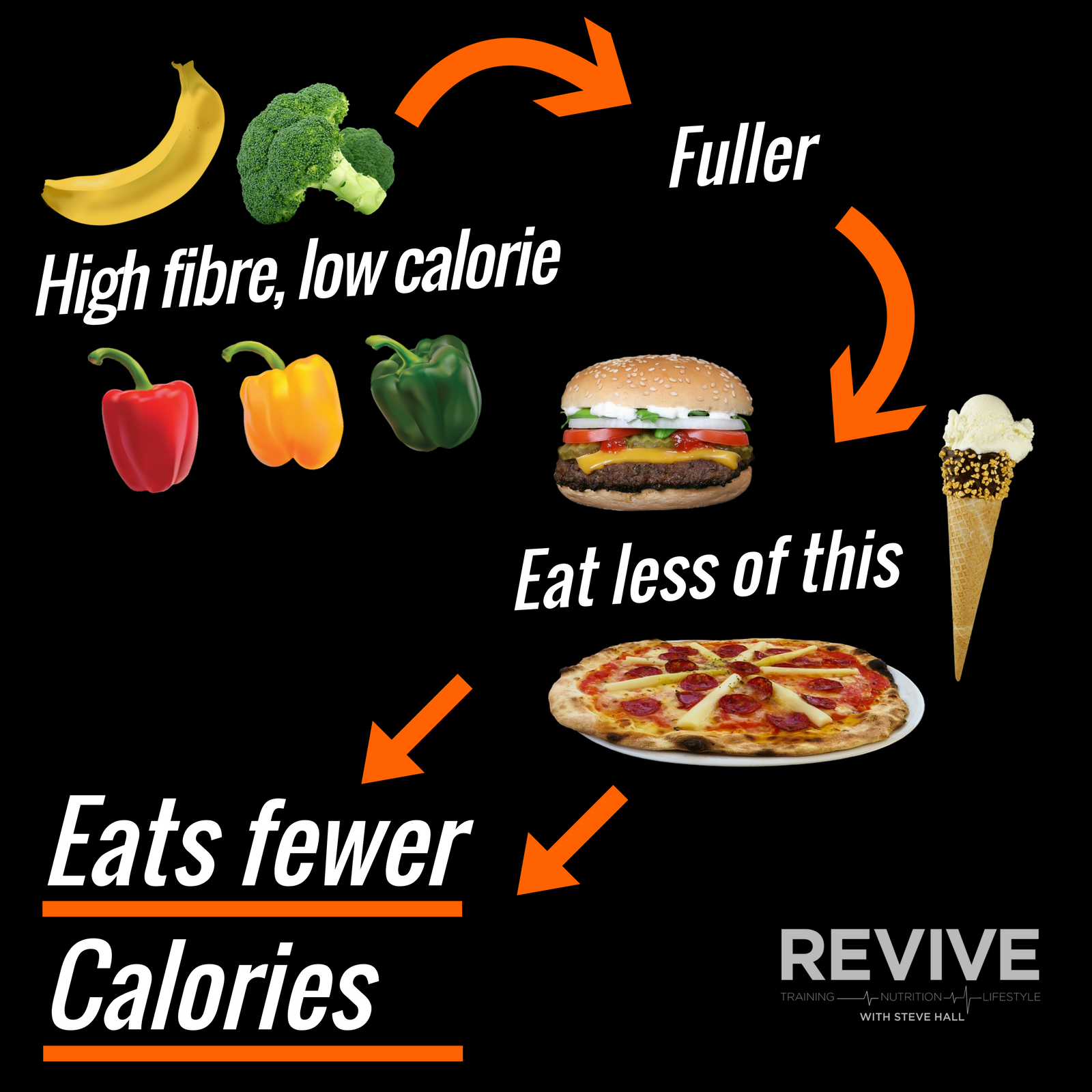

Adding vs replacing

Related to the idea of fruit and vegetable intake being a marker, it is also possible that part of the benefit of high fruit and vegetable intakes is that it serves to replace other foods in the diet. A person eating a lot of fruit and vegetables is likely to feel fuller (due to the high fibre and water content) and thus may be less likely to eat ‘junk’ foods (foods high in calories and low in nutrients) and is therefore more likely to have a lower calorie intake than a person eating fewer fruit and vegetables per day. It may be the lower intake of ‘junk’ foods or a lower calorie intake that contributes to a reduced risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease and mortality.

Publication bias

Publication bias refers to the greater likelihood of a study being published if it reports a positive result. Journals tend to be less interested in studies which report no difference. In terms of this review, it is possible that several studies have found no association between fruit and vegetable intake and future health problems but that they weren’t published.

Relative vs absolute risk

It is important to distinguish between relative and absolute risk.

For example, imagine your absolute risk of developing a certain disease is 4 in 1000 (0.04%). If a treatment reduces the relative risk by 50%, this means the 4 is reduced by 50% and your risk is now 2 in 1000. Although there has been a reduction, your absolute risk remained very low in both cases. Similarly, this review examined relative risk but it is important to remember that your absolute risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease or mortality remains very low.

Researcher recommendations vs media reporting

Unfortunately, when studies are reported by the media, there is often no mention of the conclusions made by the researchers who conducted the studies, instead a catchy, attention-grabbing headline is selected, which often misrepresents the findings. In this review, researchers were very clear that they have only shown an association between higher fruit and vegetable intakes and health, not a causal relationship and have not suggested that the current recommendation of five portions (400g) needs to change.

Government recommendations and use of evidence

The current government guidelines of five portions (400g) of fruit and vegetables per day were derived from a body of evidence indicating that this amount is the minimum amount needed per day to prevent future health problems. The current review merely confirmed what is already known, that an intake of 400g (5 portions) per day is a minimum but that higher intakes are even better, up to around 600g-800g per day (8-10 portions per day).

How much is enough?

So we come back to the question; how much is enough?

The bottom line: 5 portions per day, or 400g, remains the minimum daily intake for maintaining good health.

If you can get in more than this, that’s even better as eating more than five portions daily is associated with extra health benefits. So get munching those fruit and veggies!

What Next?

More from Emma Green (Revive Stronger intern & researcher):

Join our free facebook group or add us on snapchat (revivestronger) and ask your question there, I will respond asap. Or if you’re after a fresh training programme we have a free 4 week plan using DUP that you can download for free here.

One more thing… Do you have a friend who would love the above? Share this article with them and let me know what they think.

[bctt tweet=”Fruit and vegetable intake: how much is enough?” username=”revivestronger”]

References

1.] Aune, D., Giovannucci, E., Boffetta, P., Fadnes, L. T., Keum, N., Norat, T., … & Tonstad, S. (2016). Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality–a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. International Journal of Epidemiology.

We are a personal coaching service that helps you achieve your goals. We want you to become the best version of yourself.