Revive Stronger

Are you Screwing Up your Warm Up?

The warm up.

Simple, right?

Well, yeah, it actually is…

With that said, there are some common misconceptions about what a warm up should look like. I’ve been the guy flopping around on a foam roller, and spending far too much time stretching and doing mobility work pre-work out. I’ve also been the guy that has jumped right into my working sets before doing a second of warming up.

I wouldn’t recommend either of these strategies.

This brings up some questions:

- Is there a need to stretch and warm up before training?

- If so, what’s a good warm up look like?

- How long should it last?

- Should you do mobility work?

- Should you implement static or dynamic stretches?

All great questions, all covered here for you today.

Table of Contents

Static vs. Dynamic Stretching

I’ll make this quick, static stretching blows and dynamic is the way to go…kind of kidding, kind of not though.

Static Stretching

1.] What it is: Static stretching involves holding a muscle in it’s lengthened position for a given amount of time. An example would be doing a standing toe-touch, where you hold the toe touch for say 30 seconds.

2.] What it does: Static stretching done before training decreases performance. It can also increase range of motion, but only to a similar degree to dynamic stretching, which we’ll get to later.

3.] How it decreases performance: It decreases muscle stiffness, wait… what? That sounds like a GOOD thing? Yeah, I thought so too, but actually, the stiffer the better (“that’s what she said”). Decreased muscle stiffness is actually a BAD thing. This is because it inhibits the stretch-reflex. Ya know when you hit the bottom of a squat and you feel a little bit of a “bounce” helping you out of the hole? That’s the stretch reflex at play.

Clearly, we don’t want to miss out on that.

I’m not an analogy king like big Steve, so I’m stealing one from Dr. Zourdos:

“Think of your muscle like a rubber band. When you static stretch, you lengthen that band, and it becomes stretched out and loose. This gives you less of an ability to shoot the rubber band very effectively. Just like when your muscles are a bit less stiff, you have less spring out of the bottom of a squat (or any other movement where you’ve lengthened the primary muscle).”

Another misconception about static stretching is that it helps aid recovery.

This is false, static stretching hasn’t been shown to have any impact on recovery or DOMS. You can increase recovery by sleeping more, eating more, and by increasing blood flow to the area. Static stretching doesn’t put you to sleep, it doesn’t feed you, and it doesn’t increase blood flow to the area.

It may help you “feel better” acutely, but it’s unlikely to really provide any significant benefit for recovery.

Dynamic Stretching

I.e. the type of stretching you want to do.

1.] What it is: Dynamic stretching is stretching that uses momentum and muscular effort, but the end position is not held. An example of this would be doing front-to-back leg swings.

2.] What it does: It increases performance.

3.] How it increases performance: When you engage in dynamic stretching, you increase your core temperature, heart rate, VO2, blood flow, and potentially your muscle spindle excitation. What the hell is muscle spindle excitation you might ask? Well, muscle spindles are responsible for creating the stretch-reflex. So, if your muscle spindles are firing better (excitation), you can potentially improve your stretch-reflex, aiding performance.

This is thought to be the mechanism behind why dynamic stretching can actually mitigate the ale effects of static stretching, if done after static stretching. As I said earlier, static stretching suppresses the stretch reflex, so it makes sense that doing something that accentuates the stretch reflex (dynamic stretching) can mitigate those effects.

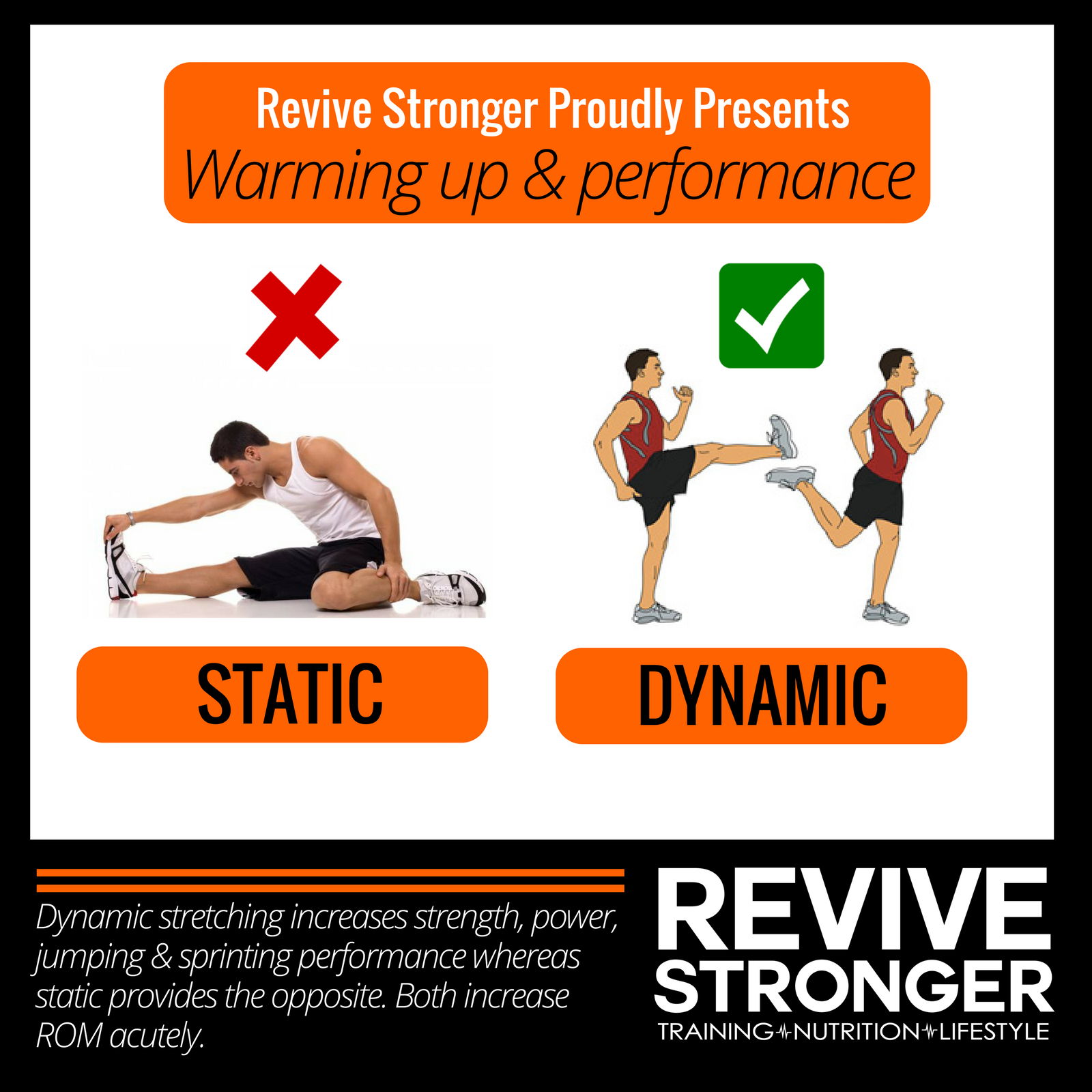

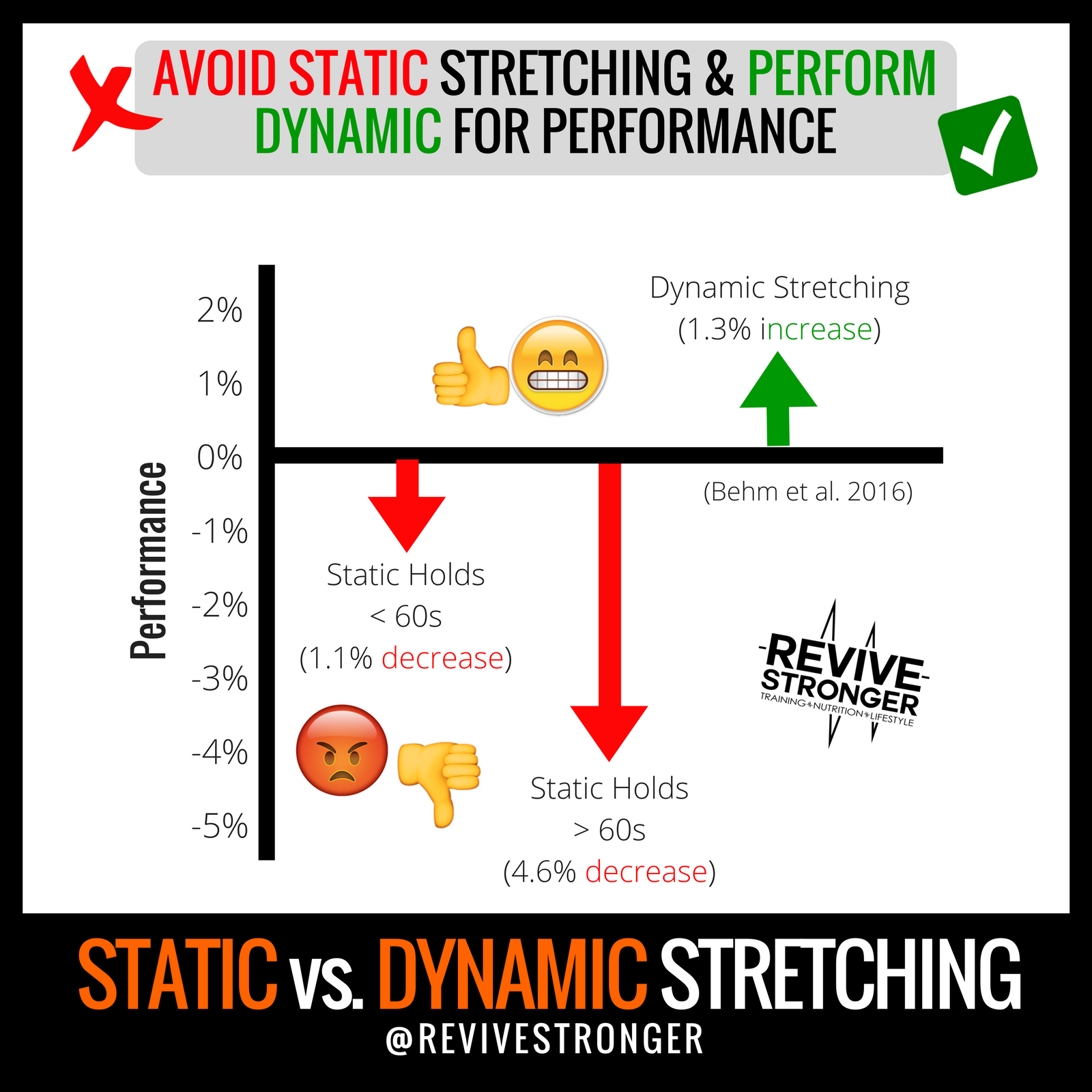

The above illustration comes from a study [1] in which they compared dynamic and static stretching.

As you can see, the data supports that dynamic stretching is likely superior for people wanting to benefit their performance, so we’ll want to stay away from any of that static shit before training… or at all… unless you really just enjoy doing it, then I’d recommend doing it as far away from your training session as possible.

With that, let’s move on to how to actually structure your warm up.

How To Structure Your Warm Up

Here’s some general guidelines (in no particular order) for a warm up:

1.] Don’t fatigue yourself

If you feel tired after your warm-up, then you’re probably f*cking around too much, wasting time and energy that could have been used eliciting a training effect.

2.] 5-15 minutes in length

This should be plenty of time to get all of the benefits from a “proper” warm up (increasing HR, body temp, blood flow, etc) without going against our previous guideline of not overfatiguing yourself for your session.

3.] Avoid static stretching

If for some reason you just really like static stretching and feel like you have to do it before training, then be sure to do dynamic stretching afterwards. This will help mitigate the negative effects of static stretching.

4.] Address any mobility restrictions while warming up

Rather than going through an entire mobility routine prior to, or after your workout, you can simply choose some dynamic stretches that aid your mobility restriction, while still providing the benefits of increased HR and body temp by doing dynamic exercises. You only need to be mobile ENOUGH, so do the least you can get away with.

5.] Specificity is king

Wanna know a great way to warm up for squats? Lighter squats.

I recommend you working up to your heavy sets with some lighter sets at very low RPE’s for all of your initial exercises for a given body part. If you just did heavy squats, you don’t need to work up to your heavier sets on a leg extension. Your quads better be damn ready to go.

So there’s some general guidelines.

Individual differences

Okay cool, but are there any situations where you may need to warm up a bit more than what’s outline above?

You bet.

These situations include:

1.] You’re dieting

When you’re dieting, it will likely take you a bit longer to feel ready to go. In my experience, taking a bit more of a prolonged warm up allows me to have more energy for my session, as I typically feel more and more energetic as I warm up when dieting.

2.] Cold environment

If for some reason your gym is really cold, then clearly, it’s going to take a bit longer for you to increase your core temperature and be ready to go.

3.] Training in the morning

Similar to the reasons for taking a longer warmup while dieting. You’ll probably feel more and more energy as you warm up in the morning as things are getting fired up for the day.

4.] Feeling a bit more beat up/achy

If you’re feeling a bit more beat up, it could take you a little longer to feel ready to train (no sh*t). I recommend going through your dynamic warm up, and then adding a few more sets to your specific warmup until you’re feeling good. I personally like adding a few more “empty bar” sets to my starting exercise before I start to add weight.

No more screwy warm ups

So are you screwing up your warm up?

Hopefully after reading this you know what to avoid and what’s a good idea when it comes to your warm up.

Following the above you’ll be:

1.] Performing at a higher level

2.] Reducing injury risk

3.] Because of 2 and 3; fitter, stronger & healthier

Go and enjoy a productive session.

What Next?

Join our free facebook group or add us on Instagram (revivestronger) and ask your question there, I will respond asap. Or if you’re after a fresh training programme we have a free 4 week plan using DUP that you can download for free here.

One more thing…

Do you have a friend who would love the above?

Share this article with them and let me know what they think.

[bctt tweet=”Are you Screwing Up your Warm Up?” username=”revivestronger”]

References

- Behm, David G., Anthony J. Blazevich, Anthony D. Kay, and Malachy Mchugh. “Acute effects of muscle stretching on physical performance, range of motion, and injury incidence in healthy active individuals: a systematic review.” Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 41.1 (2016): 1-11. Web.

We are a personal coaching service that helps you achieve your goals. We want you to become the best version of yourself.

Comments are closed.