Revive Stronger

Can you be addicted to food?

“I’m addicted to pizza”

^ quote me because it’s true

Or is it?

There is more and more research coming out regarding ‘food addiction’ and what influences how we eat on a daily basis. You have no doubt heard people quote that they’re addicted to sugar or so and so food, but can food really invoke such a strong response? Do we really find ourselves needing our INSERT FOOD ADDICTION kick?

Many foods have been compared to drugs which are often abused, including nicotine, alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine to name a few. That’s pretty scary and I am sure I don’t need to tell you that being addicted to such substances can lead to really quite dire consequences.

Therefore, to say that some foods have similar qualities is quite a dangerous claim to make if it’s not true.

And if it is true, it’s something we really should be aware of.

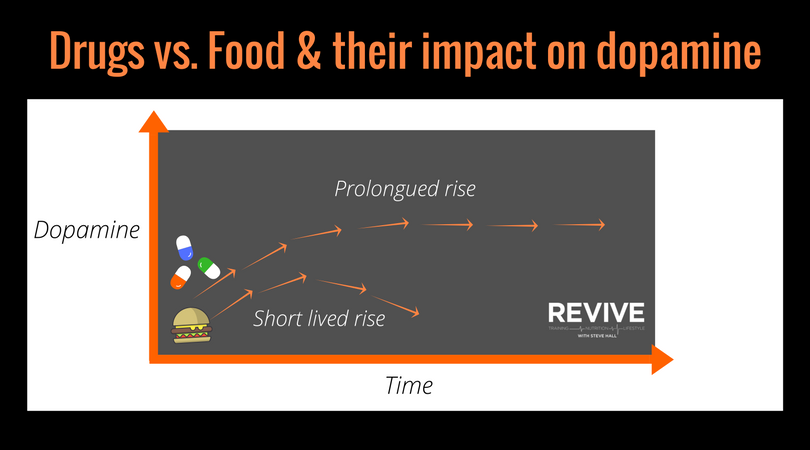

Recent research has explored whether particular properties of foods (salt, sugar etc) can stimulate similar addictive processes. These rewarding properties of foods can encourage overeating, which is known as the “food reward hypothesis”. Drugs and palatable foods share several properties and both can have powerful reinforcing effects that are influenced partly by sudden increases in dopamine in the brain, a key neurotransmitter in the brain reward system.

Simply put; eat tasty food, get a hit of dopamine (which is nice) and this reinforces your want to eat said food.

Makes sense.

This article will address whether we can be addicted to food, including a consideration of the factors influencing food intake, how the brain reward system works, the similarities in the way this system responds to food compared with drugs and how we can explain differences between individuals.

Before we get into it I want to thank Emma Green one of the interns here at Revive Stronger for doing the research for this article. Emma is a PhD student who loves lifting, eating and is and out and out geek, you can find here on instagram @veganfitnessphd.

Table of Contents

Why we eat what we eat

Why we eat what we eat involves a close interrelationship between homeostatic and nonhomeostatic factors.

1.] Homeostatic factors

Homeostatic factors are related to the body’s ability to recognise whether or not it needs extra fuel.

2.] Nonhomeostatic factors

Nonhomeostatic factors are unrelated to nutritional and energy needs. An example would be eating some cake because it’s Sandra who works on the third floors birthday and she’s always trying to feed you up and you can’t possibly say no (plus she makes the best icing ever).

We’re very well set up to maintain a healthy bodyweight from birth using our homeostatic factors, this has been replicated in animal studies too. However, the nonhomeostatic (eating food not related to real hunger) has been shown to really screw us up, and we can all relate to this, just think of Christmas day, you eat past the point of fullness.

When we eat and how much we eat

Most nonhomeostatic mechanisms are related to the brain’s reward system, particularly to dopamine.

OK so we know sometimes we eat for the sake of eating (nonhomeostatic) and at other-times we actually eat for real physiological hunger (homeostatic). How do we then decide how much to eat, and when we eat?

Deciding when to eat is influenced by perceived reward, learning, habits, convenience, opportunity, and social factors. In contrast, the decision to stop eating is controlled partly by signals from the gastrointestinal tract and partly by nonhomeostatic signals. You know like when you decide you have a second stomach, a dessert stomach, and so even though you’re full, you can still gobble down a chocolate fudge brownie ice cream with extra whipped cream.

As you can see we can easily get around our homeostatic control mechanisms, eating past the point of feeling full and this is largely down to the increasing availability of energy-dense and highly palatable foods.

Feel good foods

Almost anything we experience can be rewarding but that doesn’t mean that everything has the potential to become addictive.

According to the 5th edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), a diagnosis for addiction requires at least two of the following:

1.] Withdrawal

2.] Tolerance

3.] Use of larger amounts of the substance over longer periods

4.] Spending a great deal of time obtaining and/or using the substance

5.] Repeated attempts to quit, activities given up

6.] Continued use despite adverse consequences

The American Psychiatric Association has not recognised food addiction as either an eating disorder or a substance abuse disorder.

Interesting however is something food has in common with drugs and money is the ability to elevate our dopamine levels [1]. Over time, instead of only experiencing something as rewarding, we begin to anticipate it. This means that dopamine levels can be elevated merely as a response to the cue for food, or other rewarding substances.

Personally I know if I walk past a good coffee shop and smell the amazing aromas I get some really good feels.

Food = Drug?

As we’ve already seen drugs and palatable foods show certain similarities in terms of how they engage the brain reward system:

1.] Firstly, both activate reward-learning regions and dopamine signalling.

2.] Secondly, repeated intake of drugs or palatable foods can lead to tolerance.

3.] Thirdly, difficulties in quitting certain drugs or foods.

Although the neural effects of overeating and drug use are similar, they are not identical.

One of the key differences is that drugs stimulate a prolonged elevation of dopamine, whereas foods do not. However, there are enough similarities to suggest that both drugs and palatable food have the ability to engage the reward system in a way that promotes increased intake over time i.e. pizza tastes good, it makes me feel all warm inside, I like this, so I eat more pizza.

In the context of palatable foods, it’s therefore more useful to consider the notion of ‘abuse’ rather than ‘addiction’. Abuse merely describes a high level of consumption whereas the addiction implies dependence, of which there is very limited evidence. So in my case maybe I abuse pizza, I am not actually addicted to the cheesy goodness.

Individual difference

Genetics do play a role in how rewarding we find certain foods.

This can sometimes be the result of a dysregulation of certain homeostatic mechanisms, such as leptin signalling. Leptin is an important regulator of energy balance through influences on brain regions involved in food reward. It is released by our fat cells, and the more fat cells we have the more leptin produce, and this should result in our appetite decreasing allowing us to avoid getting fatter.

Therefore, a leptin deficiency increases appetite and food intake, plus this hormone also influences liking for food, which correlates with increases in dopamine secretion [1]. When our leptin is low, we eat more.

In addition to genetics the environment in which we live plays a role too. No doubt if you’re reading this you only need to walk down the street to find yourself surrounded by fried chicken, burgers, pizza and doughnuts. This is something a lot of us face on a daily basis is fighting the urge to visit each and every takeaway place we see.

Furthermore, we can think about our home environment too. Some of us live alone and can control what food we have in, whereas others live with partners or family members who might make our lives harder by having some delicious treats in the household. An interesting insight is the difference between my home and that of coach Pascal. I live with my girlfriend Charlotte, we both love our food and will always have a stock of chocolate or the like in, whereas Pascal doesn’t. He does this on purpose as he knows he cannot trust himself to eat these foods in moderate amounts, where as I know I can.

The tastier the food, the more difficult it becomes to turn it down and some of us live in closer proximity to these sort of things than others and respond to these cues in different ways.

Conclusions

There are several conclusions that can be drawn on the topic of food addiction.

1.] Firstly, regulating food intake is complex and involves multiple different pathways. The rewarding properties of food can override our bodies own signals to regulate hunger and bodyweight. This is a bit of a no brainer.

2.] Secondly, food and drugs engage overlapping brain reward pathways, and both stimulate the release of dopamine. However, there are fundamental differences between responses to food compared with drugs, including the lack of ability of food to stimulate elevated increases in dopamine, unlike drugs. A food is not a drug.

3.] Thirdly, addiction is determined by the subjective experience of an individual. A certain amount of dopamine release and activation of the brain reward system are not either necessary or sufficient conditions for addiction.

4.] Finally, individual experiences and genetic variation underlie differences in how the brain responds to rewarding properties of foods.

The take-home; you can’t be addicted to food but you can certainly be prone to overeating certain foods, depending on your genetic predisposition, your environment and the ability to exert restraint in the face of environmental triggers.

What Next?

Join our free facebook group or add us on snapchat (revivestronger) and ask your question there, I will respond asap. Or if you’re after a fresh training programme we have a free 4 week plan using DUP that you can download for free here.

One more thing…

Do you have a friend who would love the above?

Share this article with them and let me know what they think.

[bctt tweet=”Can you be addicted to food?” username=”revivestronger”]

[1] Alonso-Alonso, M., Woods, S. C., Pelchat, M., Grigson, P. S., Stice, E., Farooqi, S., … & Beauchamp, G. K. (2015). Food reward system: current perspectives and future research needs. Nutrition reviews, nuv002.

We are a personal coaching service that helps you achieve your goals. We want you to become the best version of yourself.

Comments are closed.